In this series of articles, Bronze Age expert Nigel Stillman discusses the Battle of Kadesh and the period of war and battle between the Hittites and Egyptians that led to it:

Ramesses II’s Battle of Kadesh (c.1274 BC)

Ramesses next campaign led to the famous Battle of Kadesh. After the battle, Ramesses ordered hieroglyphic inscriptions and battle scenes to be carved on several temples of Egypt: Karnak, Luxor, Abydos, Abu-Simble and the Ramesseum. The texts and the scenes complement each other and are full of detail, which we can use to reconstruct the battle. The Egyptians recorded many campaigns in this way, but the Kadesh records are especially extensive and detailed. It is particularly useful to look at the copies of the scenes recorded by early Egyptologists to see colours and details that have become weathered since sand was first cleared from the temples in the early 19th Century. The texts are also recorded in several surviving papyrus documents, and there are also Hittite records of the battle written on cuneiform clay tablets which were found in the archives of Hattusas.

Armies on the march

In the spring of Ramesses’ year 5, the Egyptian army marched out again from the frontier fortress of Tjel, heading along the coast until it reached the border of Amurru. Here Ramesses probably linked up with the ally contingent of Bentishina, the King of Amurru, and decided upon the order of battle for the next stage of the campaign. An elite battlegroup of chariotry and infantry was detached and sent on along the coast to outflank Kadesh. The chariots of this contingent were provided by Amurru and were destined to win renown in the coming battle. This chariotry was known as the Ne-arin, which is Canaanite meaning ‘young ones’. Their part in the plan was to secure the coast and join forces with the main army at Kadesh. Ramesses may have hoped that they would appear behind the right flank of the enemy army that was expected to be deployed on the plain of Kadesh facing Ramesses’ approach from the south. The main Egyptian force now turned inland led by Ramesses himself. Ramesses’ objective was the capture of Kadesh, which would secure Amurru and push back the frontier of the Hittite empire. Muwatalli, King of the Hittites was gathering a huge army and heading south. His objective was to defend Kadesh, repel the Pharaoh and possibly recapture Amurru.

The Egyptian army was in fact four armies: the ‘First Army of Amun (so called because it was in the lead), the Army of Ra (called P’ Ra, meaning the Ra), the Army of Ptah and the Army of Sutekh. These are often called ‘divisions’, but the Egyptian word translates as ‘army’ indicating that they were self-contained forces that included infantry and chariotry; and which could operate independently. From other documents it has been suggested that each army included at least 5000 men. There would also be a long column of baggage wagons and pack animals attached to each army.

While the Egyptians advanced between the Lebanese mountains and along the ‘valley of the cedars’ (the Bekaa valley) a huge Hittite force arrived in the vicinity of Aleppo, anciently known as Kaleb, about 100 miles north of Kadesh. This was probably the gathering place for the army; where Anatolian contingents would link up with Syrian contingents. As Egyptian texts say, ‘they covered the mountains and the valleys like locusts in their multitudes.’ The list of Hittite allied contingents given in Egyptian records shows the vast extent of the Hittite king’s empire at this time. As well as troops from the Hittite heartland and those provided according to treaty obligations by vassal kingdoms, there were mercenary contingents hired from various friendly kingdoms and tribes. As the Egyptian texts say, Muwatalli ‘left not silver nor gold in his land, but plundered all its wealth and gave it to every country to bring them with him to battle.’ The Pharaoh was with his bodyguard troops, which included household chariotry and Shardana warriors on foot, leading the army of Amun. They made camp on the hills overlooking the Orontes valley and the plain of Kadesh. Ramesses probably originally intended to wait here for the rest of his forces to arrive, before crossing the Orontes for the final advance to Kadesh. He would have perhaps expected the Hittites to be deployed in the plain to block his advance.

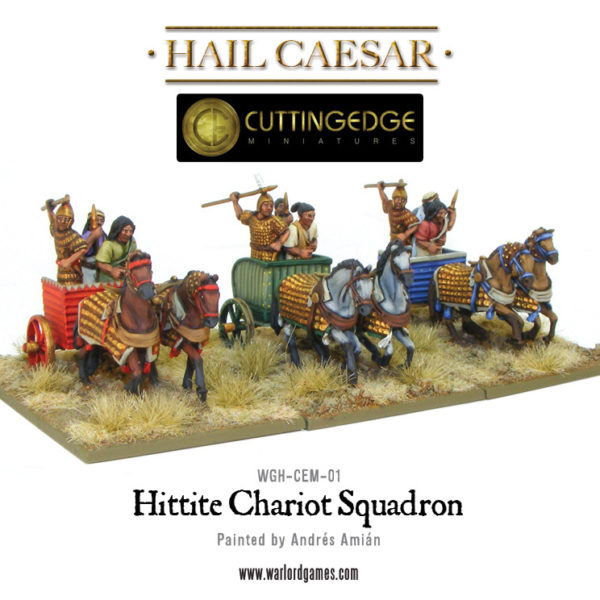

Hittite and Egyptian orders of Battle

According to Egyptian estimates, the Hittite army included about 3500 chariots (Hittite, Hurrian and Anatolian maryannu) and 37,000 infantry (mainly Hittite and Hurrian tuheyeru spearmen). Egyptian totals are not given but it is usually thought that the total Egyptian force probably exceeded 20,000 allowing for 5000 for each army corps or ‘division’. The Egyptian army probably had a greater proportion of its force as disciplined infantry than chariotry. Their chariots were lighter and faster than the Hittite types (and therefore able to get way if things went wrong!).

Egyptian records give a list of the Hittite ally contingents:

- Hatti: the Hittite heartland, the main Hittite army. Runners may have been allocated to ally chariot units.

- Naharin: the western region of Mitanni, now allied to the Hittites.

- Arzawa: a powerful west Anatolian kingdom recently vanquished and allied to Hatti.

- Dardany: the Dardanelles region, north west Anatolia, around Troy.

- Kaska: the tribes north of Hatti, usually a threat, north Anatolia; Black Sea coast.

- Masa: a central Anatolian kingdom (later Mysia.)

- Pitassa: a central Anatolian kingdom( possibly the region later known as Phrygia)

- Arwen: Ilion the city and kingdom of Troy, recently allied to the Hittites.

- Karkisa: a coastal kingdom of south west Anatolia later called Karia.

- Lukka: a coastal region of southern Anatolia later called Lycia, noted sea raiders.

- Kizzuwatna: a kingdom of southern Anatolia, later known as Que and Cilicia.

- Carchemish: the great fortress city on the bend of the Euphrates, ruled by a Hittite viceroy.

- Ugarit: powerful Phoenician city (modern Ras El Shamra.)

- Kedy: a region of northern Syria.

- Nukhashshe: a kingdom of Syria between Homs and Aleppo.

- Mushanet: an unknown region.

- Kadesh: powerful city state on the Orontes – the kingdom of Kinza (modern Tell Nebi Mend.)

- Inesa: an unknown region.

- Arvad: a Phoenician city.

- Aleppo (Khaleb): a powerful kingdom of Syria.

- Shasu scouts (let’s not forget these!)

Against these the Egyptians had:

- Pharaoh’s Household troops

- The Sherden Bodyguard

- The Ne-arun of Amurru

- The Army of Amun (HQ Thebes)

- The Army of Ra (HQ Heliopolis)

- The Army of Ptah (HQ Memphis)

- The Army of Sutekh (HQ Pi-Ramesses)

- Some contingents of local overseers of foreign countries responsible for scouting.

Tactics of deception- the Hittites set a trap

Early next day, Ramesses advanced as far as the ford across the River Orontes at the town of Shabtuna (modern Ribla.) Scouts probing ahead of the Egyptian army to locate the Hittites brought in two Shasu tribesmen. They were brought to the Pharaoh and revealed that the way to Kadesh was open. The Shasu claimed to be deserters from the Hittite army, and they had good news for the Pharaoh: their tribal chiefs wished to change sides and join Ramesses. The Pharaoh asked, ‘where are they?’ and the Shasu replied, ‘they are where the Hittite King is, in the land of Aleppo, north of Tunip. He fears you too much to come south now that you are going north.’ As the Egyptian records tell, ‘but the Shasu said these words falsely, since it was the Hittite King who sent them to spy out where Ramesses was so as to prevent him making ready to fight.’ This was a very clever ploy and one that has been used many times since to give deceptive intelligence to the enemy. The key misleading information is given indirectly through routine questioning, lending it authenticity. The Egyptians assumed the Hittites were still a long way off and relaxed their vigilance. Ramesses was suddenly presented with an opportunity to seize the initiative and reach Kadesh before the Hittites arrived. If the city fell to assault or surrendered, then his objective would be gained without even having to fight the main Hittite army. Indeed, the Hittite King might even march home rather than try to dislodge the Egyptians from Kadesh. Muwatalli must have known about Ramesses’ youthful and impetuous temperament and exploited it brilliantly.

Ramesses, together with his bodyguard and the Army of Amun, crossed the ford and advanced rapidly northwards towards Kadesh, where they began to make a large encampment, surrounded by a palisade of shields. The army must have brought forward ox drawn wagons loaded with tents and supplies, and water carts and various other equipment including a field chariot repair workshop, since these are all shown within the unfinished camp in the battle scenes. The Hittite deception plan had not only enticed the Pharaoh forward with undue haste but also stretched out the column, created long gaps between the marching armies, completely disrupting any prudent order of march. While the camp was being set up to the north-west of the great mound on which stood the mighty walled city of Kadesh, a scout belonging to the Pharaoh’s own household troops brought in two captured Hittite scouts. They were dragged into the presence of Pharaoh where they were beaten with rods and forced to talk. They revealed that they were Hittite scouts sent to spy on the Egyptian army. Ramesses asked; ‘where is the Hittite King himself; behold I have heard he is in the land of Aleppo…?’ They replied that the Hittite King had already arrived with all his vast army, ‘more numerous than the sand of the shore. Behold they stand armed and ready to fight behind Old Kadesh!’ The Hittite deception was revealed but it had worked well for long enough to draw the Egyptian army into the trap.

Ramesses called an immediate council of war and berated his staff officers; ‘Now look; I have heard in this very hour from these two scouts of the Hittite King that he has come with the many ally contingents that are with him, men and horses as many as the sand, and they stand concealed behind Kadesh…and my garrison commanders and those chiefs under whose authority are the lands of Pharaoh were unable to tell us that they had come!’ Ramesses clearly blamed the intelligence gathering effort (or rather lack of it) of the local chiefs and governors of Egyptian held territories. For the Hittites to have moved a vast army 100 miles south would have taken a few days and so should have been discovered well in advance of the battle zone. Now let us remember the battlegroup Ne-arin, which had set off along the coast. Perhaps as they reached the place where they were due to turn inland, their scouts probably found out about the Hittite move southward and moved rapidly on initiative. This would explain their subsequent arrival in the nick of time. Several despatch riders and officers in chariots including the vizier himself, set off immediately to hasten the other armies as they marched on the road to the south of Shabtuna.

Read the other Sections of this article:

History: The Battle of Kadesh part 1

History: The Battle of Kadesh part 2

History: The Battle of Kadesh part 3

History: The Battle of Kadesh part 4

History: The Battle of Kadesh part 5