At the outbreak of the Napoleonic wars the French light infantry was the finest in Europe. They could best the fierce obedience of the Germans and Dutch with their high level of independence and initiative, those of the Spanish and Italians through their determination and bravery and, in some situations, the British, using their own higher rate of fire, granted by their smoothbore Charleville muskets, to combat the British rifleman’s accuracy (though, at least by the end of the Peninsular war, the riflemen had proved more than a match for the French).

Organisation

There were three types of French light infantrymen (though all French infantry, even the Fusilier and Grenadier companies of the ordinary Line (Ligne) battalions, were trained to skirmish); the Chasseur (meaning hunter; these men formed the four centre companies of a Light (Légère) battalion), the Carabinier (the equivalent of the line battalion’s Grenadier, each light battalion had one company which deployed on the right flank) and the Voltigeur (meaning vaulter; Voltigeurs formed the light company in both Line and Light battalions and were deployed on the left flank, from where they could advance and spread out to form a skirmish screen across the front of the battalion).

On 1st January 1791 the French infantry was reorganised into 104 line regiments and 12 chasseur (light) battalions. By 1803 the French army had 26 Light infantry regiments (numbered 1-29 with the 11th, 19th and 20th disbanded in 1803).

In 1804, each infantry battalion, both line and light, was ordered to form one company of ninety of the battalions best shots into an elite company of skirmishers; the voltigeurs. In 1807 the Voltigeur Company was increased to 120 men.

In 1812 there were 34 light infantry regiments (numbered 1-37, with the 19th, 20th and 30th vacant).

During the hundred days campaign of 1815 there were only 15 light infantry regiments still active.

Training

The light infantry, ostensibly made up of the smallest and most agile recruits, drawn from mountainous recruitment departments, were trained to be highly independent, picking out their targets, shooting accurately and carrying out manoeuvres at a fast pace. When skirmishing, the infantry company, usually divided into two sections, would be split into three (the centre section with bayonets fixed).

Their independence and the emphasis in their training that they rely on their own initiative and intelligence led to a breed of fast thinking, fast moving and aggressive skirmishes who formed the van of the French army in many of its campaigns and battles (as an example both Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte were primarily stormed by the men of the 1st and 13th light infantry regiments).

But by 1813, with so many men lost in the Russian retreat, and the new rapid recruiting programme leaving little time for training, the quality of the French light infantry rapidly decreased. Thus in the German and French campaigns of 1813-1814 the light infantry was far less effective than it had been in the earlier years of republic and empire.

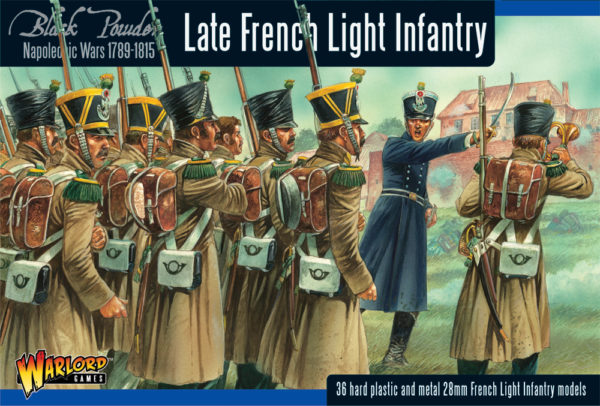

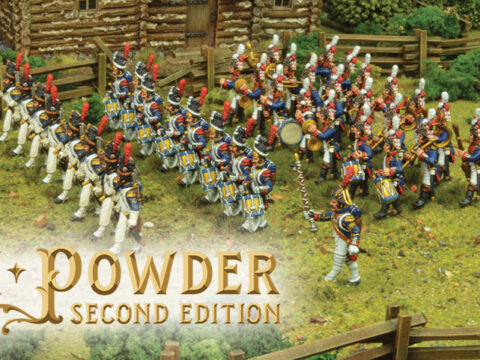

Uniform

Light Infantry wore jackets of the same dark blue as the line infantry, but with blue cuffs and facings as well; all piped with white. The collars of the Chasseurs and Carabiniers were red, while those of the Voltigeurs were yellow.

The men wore blue trousers with hessian style black gaiters, though on campaign they often wore white or grey trousers.

During the years of Empire (1804-1814) all light infantrymen wore epaulettes; red for Carabiniers and green for Chasseurs and Voltigeurs. But in 1815 only the Carabiniers and Voltigeurs wore them.

Headgear too changed over time. Between 1808 and 1811 the Chasseurs and Voltigeurs wore shakos with cords; white for the Chasseurs and yellow (tipped with green) for the Voltigeurs. They also wore a tall plume, yellow for the Voltigeurs, Green for the 1st Chasseur Company, sky blue for the 2nd, orange or pink for the 3rd and violet for the 4th. The Carabiniers wore bearskins with a red cord, but no brass plate. Their plumes, positioned to the side of the bearskin, were also of red.

In 1812 headgear changed slightly. The Chasseurs no longer wore tall plumes; instead they head spherical pompoms, though of the same colour as before. The Voltigeurs wore extended pompoms (spherical with a tuft at the top) of yellow. The Carabiniers had their bearskins replaced by shakos, the same as the Voltigeurs but with red pompom and cord.

All were armed with smoothbore Charleville muskets.

Officially the Carabiniers had all been equipped with sabers briquetes, while unofficially the Voltigeurs and Chasseurs also carried them. On 27th October 1807 a decree was issued forbidding the Chasseurs and Voltigeurs to continue carrying these short infantry swords. While the majority of Chasseurs gave up their sabers, the Voltigeurs, seemingly, hung on to theirs. The order was again repeated in 1815.

Regiment Listing

Here is a list of the 37 light infantry regiments that existed between 1791 and 1815, with details on when they were disbanded, reraised, any battle honours and (in brackets) which of the major battles of the hundred days campaign they were involved in

1st – (Ligny and Waterloo). Battle honours – Ulm 1805, Jena 1806 and Friedland 1807

2nd – (Ligny and Waterloo)

3rd. Battle honours – Eckmuhl 1809, Essling 1809 and Wagram 1809

4th – (Ligny and Waterloo). Battle honours – Ulm 1805 and Friedland 1807

5th – (Waterloo). Battle honours – Wagram 1809

6th – (Ligny and Waterloo). Battle honours – Marengo 1800, Ulm 1805, Jena 1806, Eylau 1807, Friedland 1807, Essling 1809 and Wagram 1809

7th. Battle honours – Jena 1806, Eylau 1807, Eckmuhl 1809, and Wagram 1809

8th – (Wavre). Battle honours – Wagram 1809

9th – (Ligny). Battle honours – Ulm 1805, Friedland 1807, Essling 1809, and Wagram 1809

10th. Battle honours – Ulm 1805, Austerlitz 1805, Jena 1806, Eylau 1807, Eckmuhl 1809, Essling 1809 and Wagram 1809

11th – disbanded in 1803 and reraised in 1811 – (Ligny and Wavre)

12th – (Ligny). Battle honours – Friedland 1807

13th – (Waterloo). Battle honours – Austerlitz 1805, Jena 1806, Eylau 1807, Eckmuhl 1809, and Wagram 1809

14th. Battle honours – Wagram 1809

15th – (Ligny and Wavre). Battle honours – Austerlitz 1805, Eckmuhl 1809 and Wagram 1809

16th. Battle honours – Jena 1806, Eylau 1807, Friedland 1807, Essling 1809, and Wagram 1809

17th. Battle honours – Ulm 1805, Austerlitz 1805, Essling 1809, and Wagram 1809

18th. Battle honours – Ulm 1805 and Wagram 1809

19th – disbanded in 1803 and reraised in 1814

20th – disbanded in 1803

21st. Battle honours – Essling 1809 and Wagram 1809

22nd. Battle honours – Wagram 1809

23rd. Battle honours – Wagram 1809

24th. Battle honours – Austerlitz 1805, Jena 1806, Eylau 1807, Eckmuhl 1809, Essling 1809, and Wagram 1809

25th. Battle honours – Ulm 1805, Jena 1806, Eylau 1807, Friedland 1807, Essling 1809, and Wagram 1809

26th – (Ligny). Battle honours – Ulm 1805, Austerlitz 1805, Jena 1806, Eylau 1807, Eckmuhl 1809, Essling 1809, and Wagram 1809

27th. Battle honours – Austerlitz 1805, Jena 1806, Friedland 1807, Essling 1809, and Wagram 1809

28th. Battle honours – Essling 1809 and Wagram 1809

29th

30th – disbanded in 1803, there was no 30th regiment during the Empire

31st – raised in 1804

32nd – raised in 1808 from Italians (Grand Duchy of Tuscany)

33rd – raised in 1808 from provisional regiment, in 1809 disbanded and re-raised in 1810 from Dutch 34th – raised in 1811

35th – raised in 1812 from 1st Regiment de la Mediterranean (formed in 1810)

36th – raised in 1812 from Regiment de Belle-Ile (formed in 1811) 37th – raised in 1812

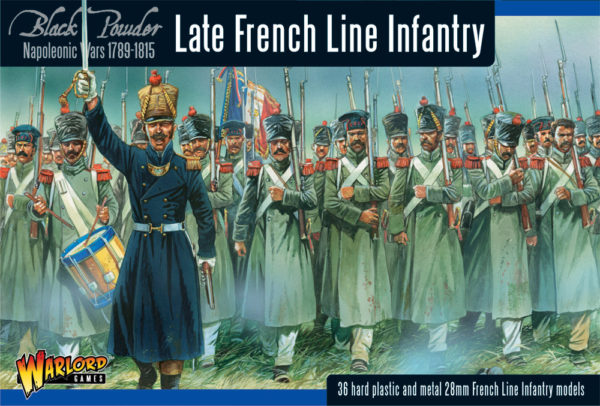

Of course the Light Infantry fought alongside their comrades in the Line Infantry:

Bibliography

French Light Infantry Regiments and the Colonels Who Led Them 1792-1815 by Tony Broughton

French Infantry of the Napoleonic Wars 1805 – 1815

Article written by Benjamin Sharkey